Read This Excerpt From John Milton's Paradise Lost

Why you should re-read Paradise Lost

The greatest epic poem in the English language language, John Milton's Paradise Lost, has divided critics – just its influence on English literature is second only to Shakespeare's, writes Benjamin Ramm.

M

Milton'southward Paradise Lost is rarely read today. But this epic poem, 350 years old this month, remains a piece of work of unparalleled imaginative genius that shapes English literature even now.

In more than than x,000 lines of blank verse, it tells the story of the war for heaven and of human being's expulsion from Eden. Its dozen sections are an ambitious endeavour to encompass the loss of paradise – from the perspectives of the fallen angel Satan and of man, fallen from grace. Even to readers in a secular age, the poem is a powerful meditation on rebellion, longing and the desire for redemption.

Despite being born into prosperity, Milton's worldview was forged by personal and political struggle. A committed republican, he rose to public prominence in the ferment of England's bloody civil state of war: 2 months later the execution of Male monarch Charles I in 1649, Milton became a diplomat for the new republic, with the title of Secretary for Foreign Tongues. (He wrote poetry in English, Greek, Latin and Italian, prose in Dutch, German, French and Castilian, and read Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac).

Milton gained a reputation in Europe for his erudition and rhetorical prowess in defence of England'south radical new authorities; at dwelling he came to be regarded as a prolific advocate for the Republic cause. But his deteriorating eyesight limited his diplomatic travels. By 1654, Milton was completely blind. For the final 20 years of his life, he would dictate his poetry, letters and polemical tracts to a series of amanuenses – his daughters, friends and fellow poets.

Milton is shown dictating Paradise Lost to his daughters in this engraving after a painting by Michael Munkacsy (Credit: Alamy)

In Paradise Lost, Milton draws on the classical Greek tradition to conjure the spirits of bullheaded prophets. He invokes Homer, author of the first not bad epics in Western literature, and Tiresias, the oracle of Thebes who sees in his mind's center what the physical eye cannot. As the philosopher Descartes wrote during Milton's lifetime, "information technology is the soul which sees, and non the middle". William Blake, the almost brilliant interpreter of Milton, subsequently wrote of how "the Eye of Imagination" saw across the narrow confines of "Unmarried vision", creating works that outlasted "mortal vegetated Eyes".

Clever devil

When Milton began Paradise Lost in 1658, he was in mourning. It was a year of public and private grief, marked by the deaths of his second wife, memorialised in his cute Sonnet 23, and of England's Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, which precipitated the gradual disintegration of the commonwealth. Paradise Lost is an attempt to make sense of a fallen world: to "justify the ways of God to men", and no dubiety to Milton himself.

But these biographical aspects should not downplay the centrality of theology to the poem. As the critic Christopher Ricks wrote of Paradise Lost, "Art for art's sake? Art for God's sake". One reason why Milton is read less now is that his religious lexicon – which sought to explain a 'fallen' globe – itself has fallen from use. Milton the Puritan spent his life engaged in theological disputation on subjects every bit diverse as toleration, divorce and conservancy.

John Martin'south 1825 painting depicts Pandemonium, the capital letter of Hell in Paradise Lost (Credit: Alamy)

The verse form begins with Satan, the "Traitor Angel", bandage into hell afterward rebelling against his creator, God. Refusing to submit to what he calls "the Tyranny of Heaven", Satan seeks revenge past tempting into sin God's precious creation: man. Milton gives a vivid account of "Man'south Get-go Disobedience" before offering a guide to salvation.

Ricks notes that Paradise Lost is "a violent argument virtually God's justice" and that Milton's God has been accounted inflexible and brutal. Past contrast, Satan has a dark charisma ("he pleased the ear") and a revolutionary need for self-determination. His speech is brindled with the language of democratic governance ("free choice", "full consent", "the popular vote") – and he famously declares, "Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven". Satan rejects God'due south "splendid vassalage", seeking to live:

Complimentary, and to none accountable, preferring

Hard liberty before the piece of cake yoke

Of servile Pomp.

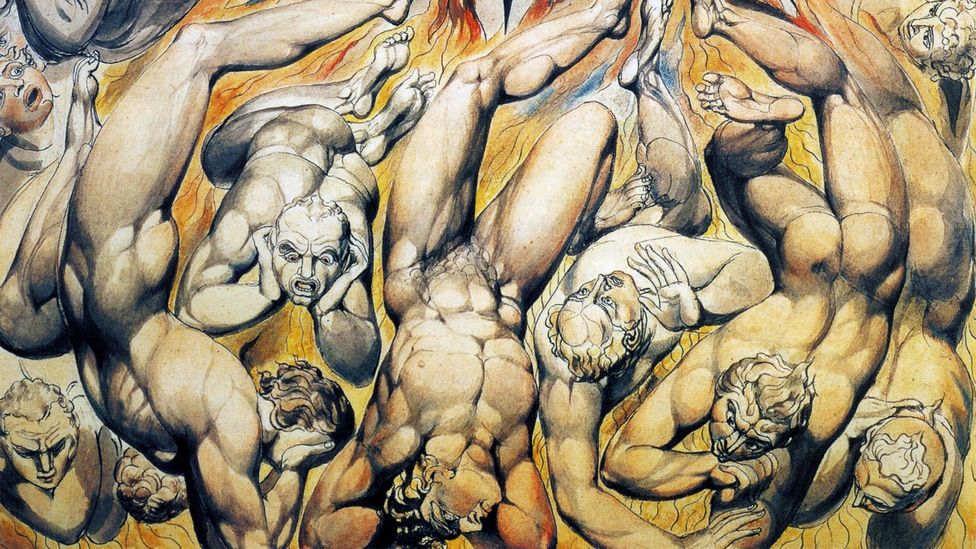

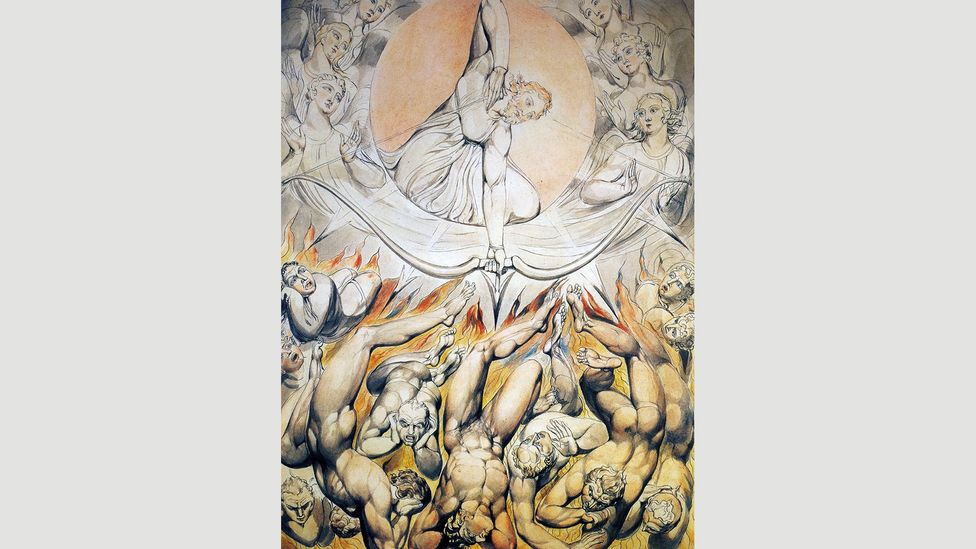

Nonconformist, anti-institution writers such as Percy Shelley found a kindred spirit in this depiction of Satan ("Milton's Devil every bit a moral being is… far superior to his God", he wrote). Famously, William Blake, who contested the very thought of the Autumn, remarked that "The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at freedom when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil'due south political party without knowing information technology".

Like Cromwell, Milton believed his mission was to usher in the kingdom of God on earth. While he loathed the concept of the 'divine correct of kings', Milton was willing to submit himself to God in the belief, in Benjamin Franklin'due south words, that "Rebellion to Tyrants Is Obedience to God".

William Blake, who chosen Milton 'a true Poet', produced several sets of illustrations for Paradise Lost in the early 19th Century (Credit: Alamy)

Although discussion of Paradise Lost oftentimes is dominated by political and theological arguments, the poem also contains a tender commemoration of love. In Milton'due south version, Eve surrenders to temptation in part to be closer to Adam, "the more than to draw his love". She wishes for the freedom to err ("What is religion, honey, virtue unassayed?"). When she does succumb, Adam chooses to bring together her: "to lose thee were to lose myself", he says:

How can I alive without y'all, how forgo

Thy sweet converse and dearest and then dearly joined,

To alive again in these wild wood forlorn?

Should God create another Eve, and I

Some other rib afford, yet loss of thee

Would never from my middle.

Canon fodder

When Paradise Lost was published in London in 1667, Milton had fallen out of favour. Just months earlier the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in May 1660, he had published a pamphlet denouncing kingship. Now Milton was scorned, his writings were burned, and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London – but narrowly escaping execution later the intercession of a boyfriend poet, Andrew Marvell.

Yet Paradise Lost gained immediate acclaim fifty-fifty among royalists. The poet laureate John Dryden reworked Milton's epic, casting Cromwell – a regicide with dictatorial tendencies – in the role of Satan. Samuel Johnson ranked Paradise Lost among the highest "productions of the human listen".

Romantic writers celebrated Milton both for his stance against censorship ("Requite me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely co-ordinate to conscience", Milton wrote in the pamphlet Areopagitica), and for his innovative poetic grade, which was suggestive, allusive and free from what he chosen "the troublesome and modern bondage of rhyming". Paradise Lost inspired Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, while Wordsworth began his famous sonnet London, 1802 with a plea: "Milton! grand shouldst exist living at this hour: England hath need of thee".

Simply not all critics were and so favourable. The 20th Century brought us the 'Milton Controversy', during which his legacy was fiercely contested. His detractors included poets TS Eliot and Ezra Pound (who wrote that "Milton is the worst sort of toxicant"), while back up came from both devout Christians (similar CS Lewis) and atheists (including William Empson, for whom "The reason why the verse form is and then good is that information technology makes God so bad"). Malcolm 10 read Paradise Lost in prison, sympathising with Satan, while AE Housman quipped that "malt does more than than Milton can / To reconcile God'due south ways to human being".

In recent years, Paradise Lost has constitute new admirers. Milton is "our greatest public poet", says writer Philip Pullman, whose acclaimed trilogy His Nighttime Materials was inspired by the verse form (and takes its title from Book II, line 916). Pullman loves Milton's brazenness – his declaration that he will create "Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhyme" – and his musicality: "No one, not even Shakespeare, surpasses Milton in his command of the sound, the music, the weight and taste and texture of English words". Pullman has declared: "I am of the Devil's party and know it".

Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials takes its name from Paradise Lost; the start book in the trilogy, The Golden Compass, was turned into a movie in 2007 (Credit: Alamy)

Milton'southward enemies regarded his incomprehension as divine retribution, but his condition enhanced his astute musical sensibility. Pullman is enchanted by the poem's "incantatory quality", and implores readers to experience it aurally: "Rolling swells and peels of audio, powerful rhythms and rich harmonies… that very form casts a spell". Paradise Lost makes an fantabulous audio volume.

It is said that Milton had fevered dreams during the writing of Paradise Lost and would wake with whole passages formulated in his mind. The first time I read the poem, I did so in a single sitting, overnight – similar Jacob wrestling with the Angel until morning. Each re-reading brings intoxication, exhilaration and exhaustion, and vindicates Milton's observation: "The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Sky."

This story is a part of BBC Uk – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a fourth dimension. Readers outside of the UK can encounter every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage ; you as well tin can run into our latest stories by post-obit u.s.a. on Facebook and Twitter .

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you lot take seen on BBC Civilization, head over to our Facebook page or message united states on Twitter .

And if you liked this story,sign upward for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20170419-why-paradise-lost-is-one-of-the-worlds-most-important-poems

0 Response to "Read This Excerpt From John Milton's Paradise Lost"

Post a Comment